Calculating NMR shielding tensors using pseudopotentials

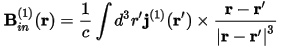

A uniform external magnetic field, B, applied to a sample induces an electric current. In an insulating non-magnetic material, only the orbital motion of the electrons contributes to the this current. In addition, for the field strengths typically used in NMR experiments, the induced electric current is proportional to the external field, B. This first-order induced current, j(1)(r), produces a non-uniform magnetic field:

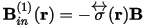

The shielding tensor, σ(r), connects the induced magnetic field to the applied magnetic field:

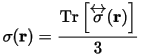

and the isotropic shielding is given by:

All-electron magnetic response with pseudopotentials

Information about σ(r) at nuclear positions can be obtained from NMR experiments. In CASTEP, the first-order induced current, j(1)(r), is calculated and then used to evaluate the induced magnetic field, B(1) through Eq. 42. Calculations are performed with the gauge-including projector augmented-wave method (GIPAW) developed by Pickard and Mauri (2001). The projector augmented-wave formalism originally introduced by Blöchl (1994) makes it possible to obtain expectation values of all-electron operators in terms of pseudo-wavefunctions coming from a pseudopotential calculation and the GIPAW formalism reconciles the requirement of translational invariance of the crystal in a uniform magnetic field with the localized nature of Blöchl's projectors. The theory was initially applied with Troullier-Martins norm-conserving pseudopotentials (Pickard and Mauri, 2001) and has been extended subsequently to the case of ultrasoft pseudopotentials (Yates, 2007).

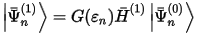

The first-order perturbation wavefunction, Ψ(1):

is proportional to the magnetic perturbation, H(1), which, in pseudopotential calculations, contains a contribution due to the non-locality of the pseudopotential, in addition to the usual term:

Calculation of perturbed wavefunctions

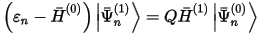

In order to obtain the first-order perturbation wavefunction Ψ(1), the application of the Green function in Eq. 46 is performed in CASTEP by solving a system of linear equations:

where Q is the projection operator onto the unoccupied Hilbert subspace. The system is solved by a conjugate gradient minimization scheme, whereby the tedious summation over unoccupied states is avoided. The method is, thus, comparable in computational cost to the calculation of the ground-state electronic structure.

NMR properties of molecules and crystals

The calculation of the induced current involves evaluation of expectation values of the position operator, whose definition for extended systems is not straightforward. Two approaches have been developed (Pickard and Mauri, 2001) and implemented in CASTEP. For translationally invariant systems with well-defined Blöch vectors, k, the application of the position operator can be reduced to calculating the gradient in k-space. Alternatively, for finite systems, which are represented by supercell structures (a molecule in a box) in CASTEP, one can apply a real-space representation of the position operator. The artificial periodicity imposed on the system causes the position operator to acquire a sawtooth shape. Thus, in the vicinity of the box boundaries, the position operator is distorted. Because of this, a sufficiently large supercell must be constructed so that the electronic density does not reach the regions where the position operator behaves unphysically. This condition is easily satisfied by the usual physical requirement that the molecules in neighboring boxes do not interact.

NMR shielding tensor

Finally, the induced magnetic field, B(1), is calculated from the induced current and its value at the nuclear position determines the NMR shielding tensor. The calculated tensor is rather sensitive to numerical errors in both the unperturbed wavefunction, Ψ(0), and its first-order perturbation,Ψ(1), so the convergence requirements for NMR calculations are more stringent than, for example, routine band structure calculations. To obtain reliable results, the convergence of the wavefunction with respect to the number of basis functions (plane waves) must be ensured and a well-converged conjugate gradient procedure put in place to determine the coefficients of the plane waves. Apart from that, in calculating solid-state NMR properties (a small unit cell as opposed to a molecule in a box) the convergence of the k-space sum over the Brillouin zone must be achieved. The NMR observables are not particularly sensitive to uncertainties in the ground-state density distribution in the system, which determines the unperturbed Hamiltonian. Here, the usual convergence criteria for self-consistent DFT calculations are sufficient.

Chemical shift (or shielding) can be calculated for paramagnetic materials where the total spin is zero, even if a spin-polarized treatment is applied. This opens the possibility of using the DFT+U method as implemented by Shih and Yates (2017). The nonlocal Hubbard correction potential has been reexamined in order to comply with the gauge-including projector augmented-wave transformation under an external uniform magnetic field. The resulting expression is suitable for chemical shift calculations using both norm-conserving and ultrasoft pseudopotentials in the projector augmented-wave scheme. As a result more accurate results can be obtained for transition metal and rare earth oxides.

It is important to examine the results and establish that the solution is indeed paramagnetic. If the total spin of the final state is non-zero, or the spin arrangement is antiferromagnetic, the results are likely to be meaningless.

Sensitivity of NMR to calculation parameters

NMR properties calculations are very sensitive to the number of k-points in the Brillouin zone. It is hard to construct a general rule for the number of k-points required, so it is recommended that you carry out convergence tests. An example convergence test for gallium phosphide is given below (these results are obtained for the experimentally observed structure of cubic GaP, ultra-fine settings, on the fly generated ultrasoft pseudopotentials, PBE functional).

Table 1. Convergence test for GaP

| k-point mesh | chemical shift (ppm) | |

|---|---|---|

| P | 2 × 2 × 2 | -578.60 |

| 4 × 4 × 4 | 302.72 | |

| 8 × 8 × 8 | 376.18 | |

| 12 × 12 × 12 | 375.45 | |

| 16 × 16 × 16 | 375.34 | |

| Ga | 2 × 2 × 2 | 920.61 |

| 4 × 4 × 4 | 1335.72 | |

| 8 × 8 × 8 | 1352.50 | |

| 12 × 12 × 12 | 1352.21 | |

| 16 × 16 × 16 | 1352.20 |

It follows from Table 1 that a grid of at least 12 × 12 × 12 is required to achieve convergence of the chemical shift to within 1-2 ppm, and finer grids might be needed to achieve higher accuracy.

NMR properties are very sensitive to atomic positions, which makes NMR such a useful experimental tool for structure analysis. This implies that it is highly recommended to perform a geometry optimization run prior to the NMR calculation. If the structure of a crystal or molecule under investigation is obtained from an experimental study, it is advisable to optimize positions of hydrogen atoms first of all. If the forces on heavy atoms as reported by CASTEP are high (in excess of 1 eV/Å) then complete structure optimization is recommended.